Canada Struggles with Melting Permafrost as Climate Warms

In 2006, reduced thickness of ice roads forced the Diavik Diamond Mine in Northern Canada to fly in fuel rather than try to transport cargo across melted pathways, at an extra cost of $11.25 million.

The mountain pine beetle outbreak in British Columbia—fueled by higher winter temperatures that allow insects to survive—expanded in recent years to be 10 times greater than any previously recorded outbreak in the province. Mortality rates of sockeye salmon, meanwhile, have increased because of higher water temperatures in the Fraser River.

These examples are among many in Canada’s national climate assessment—an overview from the national government of existing climate science affecting the country. It also includes government and industry adaptation activities, such as new electricity forecasts for hydropower because of projected water flow shifts.

While focused on Canada, the overview holds relevance for global industries, such as oil sands developers potentially affected by floods and shippers traversing Canadian waterways, analysts say.

The report released by Natural Resources Canada—a third national assessment of climate impacts in the country—also provides more detail than a regional chapter on North America in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change documents released this year.

“It is important that Canadian scientists summarize the Canadian literature for Canadian decisionmakers,” said Paul Kovacs, president and CEO of Property and Casualty Insurance Compensation Corp. The report released last month included more than 90 authors and 115 expert reviewers, and analysis from more than 1,000 studies.

Running on fast-forward

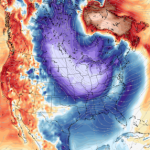

Many of the report’s climate statistics are stark. Between 1950 and 2010, Canada’s average air temperature over land warmed about double the global average, or about 1.5 degrees Celsius.

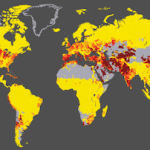

The country as a whole has become wetter, while sea levels on the country’s coasts rose about 21 centimeters between 1880 and 2012.

The impacts are apparent in Canada’s north, the report says, where melting permafrost and glaciers are changing the landscape quickly. “Glaciers in Yukon have lost about 22% since the 1950s,” the report notes. Lake ice—critical for activities such as ice hockey—may decrease in duration by roughly a month by midcentury, according to scientists.

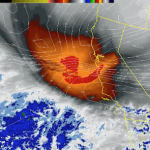

Earlier this year, Canada’s insurance industry reported that 2013 was the costliest ever because of claims from extreme weather, with losses rising above $3 billion (ClimateWire, Jan. 22).

On the other hand, climate change may help some food production and industries that can benefit from northward expansion such as maple syrup developers. “Total biomass of production from wild, capture fisheries in Canada [are] expected to increase due to climate-induced shifts in fish distributions,” the report states.

Industries need more guidance

In another small example of how warming plays out on the ground, the report notes that the golf industry in the Toronto region may benefit, as warmer weather may allow the golf season to extend by as much as seven weeks in the 2020s.

Blair Feltmate, an associate professor at University of Waterloo, welcomed the analysis but said it didn’t go far enough in outlining solutions for industries and communities. “It’s not what’s in the report … it’s what’s not in the report,” he said.

He noted, for instance, that melting permafrost in mining areas is putting industrial tailings ponds at risk of seepage. What would be more helpful is for industries to be provided with an adaptation “to do” list, rather than a broad overview, said Feltmate, who is leading a more than $1 million project funded by an insurance company to implement adaptation measures in several Canadian cities.

Overall, the country is doing some things right, such as recently pledging to update flood maps that “were completely out of date,” Feltmate said. At the same time, there are still too many people working in different agencies not sharing information with one another—and provinces—about things such as flood protection options.

“There needs to be one national coordinating entity on adaptation,” he said.

Source: Scientific American

Leave a Reply