Rapid pace of changing climate gets special emphasis in new status report

Source: MinnPost.

The climate is changing more rapidly in today’s world than at any time in modern civilization. … If we look at it like we’re trying to maintain an ideal weight, then we’re continuing to see ourselves put more weight on from year to year.

— Thomas Karl, director of the National Climatic Data Center at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, as quoted in The Christian Science Monitor on Monday.

The “State of the Climate in 2013” report came out at the end of last week, offering a selection of global-warming superlatives of the most troubling kind for last year:

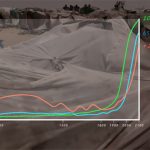

- Atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide exceeded 400 parts per million for the first time at the Mauna Loa observatory in Hawaii, whose records go back to 1958. (Yes, that’s the greenhouse-gas measure from which the climate advocacy group 350.org derived its name, in reference to the level that many scientists have set as the maximum that a livable planet Earth can sustain).

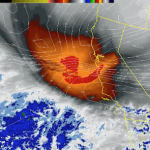

- Sea surface temperatures in the North Pacific were the warmest on record, in the absence so far of El Niño/La Niña influences.

- Record high temperatures were recorded at 20-meter depths in the Arctic permafrost of Alaska.

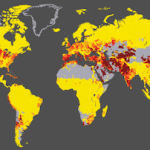

- Australia recorded its warmest year ever.

And though these measures mark extremities, they are not aberrations so much as notable examples of overall, continuing — and worsening — trends in the climate systems of a warming world, as documented in State of the Climate in 2013:

- Depending on which of four international data sets is used, 2013 ranks as either the second warmest year record or the sixth, with the global average temperature somewhere between 0.2 and 0.21 degrees C. (o.36 to 0.38 F) above the average for the period 1981 to 2010.

- Australia’s hottest-ever year also saw Argentina record its second-warmest, and New Zealand its third-warmest. A weather station at the South Pole recorded its warmest temperature in a record going back to 1957.

- Atmospheric CO2 went up 2.8 ppm to a global average of 395.3 for the year; in the Arctic, the 400 ppm mark was passed in the spring of 2012.

- Arctic sea ice extent was the sixth lowest since observations began 25 years ago; all seven of the lowest measures of sea-ice extent have occurred in the last seven years; overall, the Arctic recorded its seventh-warmest year since the early 1900s.

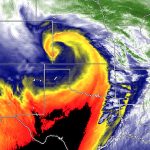

One record-setting aberration also worth noting: Though 2013 was only slightly above normal in its number of tropical cyclones, Super Typhoon Haiyan, which struck the Philippines and parts of Southeast Asia in November, generated the highest sustained wind speeds ever attributed to such storms — 196 miles per hour.

24-year, peer-reviewed series

“State of the Climate in 2013,” the 24th report in an annual series, draws on the work of 425 scientists in 57 countries; their findings are published as a peer-reviewed paper in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. (The full 262-page report can be downloaded here.)

The observations by data center director Tom Karl that appear at the top of this piece have been quoted widely in coverage of the new report, and I think there’s good reason for that.

This report marshals considerable evidence in support of the notion that the pace of climate change is not always or necessarily slow, although it can seem so when you read about projections of greenhouse-gas concentrations and temperature trends stretching out for decades, a century, or even longer.

At the same time, Karl has touched on the great disconnect between our knowledge of the problem and its causes, and our willingness to take serious and concerted action to change course. When it comes to fossil-fueled global warming we are, metaphorically speaking, a community of morbidly obese people who understand exactly where our excess pounds came from, and precisely what we need to do to take them off, and yet we think and talk and commiserate about all this at great length as we cut ourselves additional slices of banana cream pie.

Conservatism of science

Just before State of the Climate in 2013 came out, there was a National Research Council report that focused on the rapidity of warming trends in the Arctic and a process called “arctic amplification,” which is driving a warming trend at twice the pace of the overall global trend.

This got the attention of Bruce Melton, who writes about global warming at Truthout and elsewhere, and he made a point that I think is interesting to consider in the context of State of the Climate in 2013 and its distinguishing emphasis on the rapidity of change.

Melton argues that the various forms of scientific consensus on global warming — the touchstones that serious-minded, concerned people are perpetually defending from assault by the braying denialist claques — are in fact conservative assessments that almost certainly understate the pace and impacts of global warming. Excerpts, lightly compressed:

Science is a conservative industry that classically understates fact. If a scientist is wrong in his or her published findings, the scholarly journals will think twice about publishing that scientist’s work again. Science therefore systematically understates evidence.

The consensus process, like that of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), is even more conservative (underestimating) in their statements because of the large number of individual scientists who must agree on the consensus position.

Scientists are specialists. Almost all of them specialize in minute sectors of science as a whole. For large numbers of climate scientists to agree on a statement, they must be familiar with the leading edge of science that that statement discusses. In the highly compartmentalized world of research science, details of all disciplines are seldom understood by all. The consensus opinion is therefore constantly behind the leading edge of science. With a rapidly changing climate, this can be a problem.

In our old climate, we sort-of knew how it behaved. We had decades and even centuries of records to use to project changes into the future. But all of this historical data may be of much less use in the future as the baseline physics have now changed. Even more critical, the short term is now very important as tipping points may appear at any time.

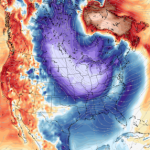

Another interesting take turned up over at climatecentral.org, where Brian Kahn focused on State of the Climate in 2013’s findings about rapid warming trends in surface sea temperatures, and on the implications for the next El Niño event.

With 2014 halfway over, there are no signs that the globe’s hot streak is ending. Data through May shows that this has been the planet’s fifth-warmest start to the year on record. Jessica Blunden, a scientist who works with the National Climate Data Center, said that preliminary data show that June’s ocean temperatures were the hottest on record, a sign that 2014 is on track to be one of the hottest years recorded.

Another factor tipping the scales in that direction is the impending El Niño, a climate phenomenon that usually boosts global temperatures. Other indicators like greenhouse gas emissions, Arctic sea ice and deep ocean heat are also likely to keep following suit.

A week earlier, Kahn’s Climate Central colleague Andrea Thompson had this to say about the next Niño:

The latest update from the Climate Prediction Center, issued Thursday, finds that conditions still aren’t quite in place to declare a full-blown El Niño, though forecasters still expect one to emerge by the fall. If and when it does, it is expected to impact weather and climate across the world and could push 2014 or 2015 to be the hottest year on record.

While the atmospheric characteristics that indicate an El Niño have been evident intermittently, they have yet to firmly take hold. Ocean surface temperatures have also fluctuated, though there is still considerable heat below the surface to fuel an El Niño, said Michelle L’Heureux, a CPC meteorologist who helps put together the monthly outlooks.

The update, issued in conjunction with the International Research Institute for Climate and Society at Columbia University’s Earth Institute, kept the chances of an El Niño being in place by later this summer and by fall to early winter at about the same as last month, 70 percent and 80 percent, respectively.

Source: MinnPost

Leave a Reply